Kathrin Isabell Rhomberg – INFINITE HORIZON

Infinite Horizon: A multi-faceted connection of past, present and future

A text by Alexandra Steinacker

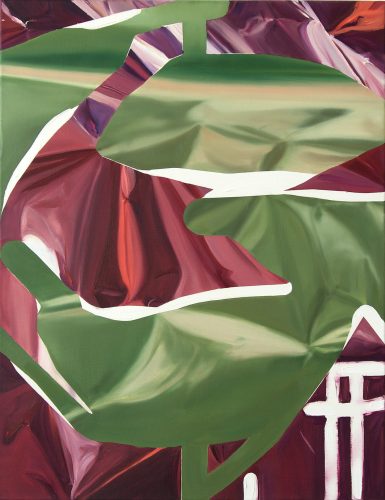

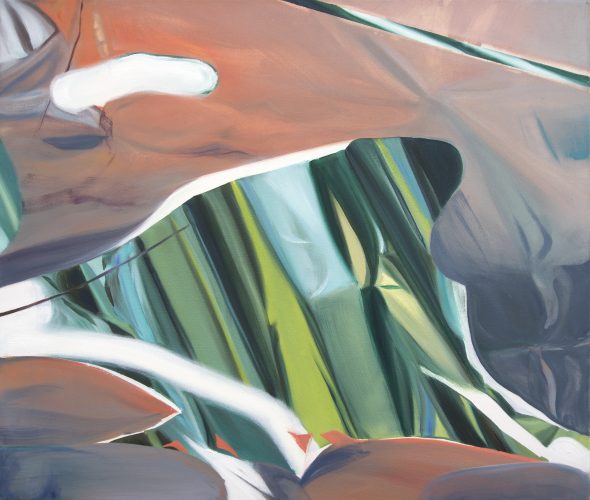

Artificial realities, abstracted nature, analog technology. Contradictory themes are present within one painting, creating a multi-faceted work that spans over time and space. Kathrin Isabell Rhomberg ignites this exploration of temporal and spatial themes through oil on canvas, including elements that relate to the composition as well as drapery in sixteenth to eighteenth-century painting, making specific reference to theories of frames, folds, and niches present in The Self-Aware Image by art historian Victor I. Stoichita. She also explores the aspect of nature, both of her home country of Austria as well as the nature scenes depicted in nineteenth-century landscape painting.

A further facet to her works is its relation to technology, playing with glitch-art aesthetics (the imagery resulting from digital malfunctions on screens, interrupting the composition), and visual qualities of the digital. In addition, she explores technology’s relation to the boundaries between organism and machine, relating to how humans interact with technology and how it has become integrated into our lives, bodies and minds in various ways. These boundaries have been explored in A Cyborg Manifesto and Staying with the Trouble, two publications by Donna Haraway, professor and prominent scholar with a feminist, postmodernist approach to technology and society, that engage with theories which I argue are also present within Rhomberg’s practice. The investigation and visual manifestation of these themes are prevalent in the young artist’s paintings and span through her works from her time at the University of Applied Arts Vienna up until the works she creates today.

Starting in the sixteenth century, a so-called “crisis of imagery” emerged in which many structures within artistic discourse were destabilized such as the patronage system, as well as the emergence of new forms of painting such as still-life, genre, and landscape painting.(I) Sociopolitical, economic, and religious circumstances led to changes in the iconography and purpose of painting, and a “religious splintering and pictural rupture” ensued as a result of these changes.(II) Victor I. Stoichita argued that a fragmented field of vision was prevalent in Italian and Flemish painting at the time which contained a dialogue between contradictory forces such as religious narratives and mundane objects, or the sacred and the profane.(III) With this, Rhomberg also fragments the viewer’s vision through her abstracted visual language, challenging the empty space of the canvas through her paint. She explores materials through a deep concentration on the mastery of the fold, depicting what could be the wrinkles of a heavy satin curtain, or even the shimmering folds of a reflective rescue blanket (also called ‘space blankets’) used when paramedics assist injured hikers in the mountains. The question prevails of what the curtain or blanket could be hiding, or what it could unveil. However, through the abstracted visual language and macro perspectives, the fold in Rhomberg’s works eludes any figurative definition and it upholds its pure materiality rendered in paint.

Delving further than a reference to human’s connection to nature through hiking and a rescue blanket, Rhomberg’s artistic practice relates to the nature prevalent in nineteenth-century painting through to her personal experiences of today. Each fold entails the endless potential for a journey to develop in any direction, an exploration with endless possibilities and infinite horizons. They contain an ambivalence of what the future holds, again eluding definition and remaining boundless, contemplating the possibility of different paths in life, not unlike the vast landscapes of Casper David Friedrich. Friedrich was a German artist active in the Romantic period of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries best known for his oil on canvas painting titled ‘Wanderer above the Sea of Fog’ (1818), in which a man in an overcoat stands perched on a rocky cliff with a contrapposto stance and a walking stick, gazing away from the viewer and out into a vast open sea of fog and mountaintops. Rhomberg’s paintings move into abstraction however they do not always evade figuration, as the connection to natural elements such as foliage or leaves, or even the silhouette of green hills and blue skies, appear in her works such as Veil (2020) orWorld away (2021). Where her pieces hold contradictions of abstract and figurative, or reference art historical contradictions of the sacred and profane, they also contain the contradiction of the artificial and the natural. The abstracted materiality of her works contradicts the shapes and colors found in nature, thus Rhomberg redefines them, pulling them into her liminal space of the endless possibilities, of the boundless fold.

The connection between man, nature, and technology remains in a permanent tilt through the instability, an unevenness, of our planet, a once stable base for humanity.(IV) Theorized by Anselm Franke and Diedrich Diederichsen, a conceptual and behavioral shift emerged through humanitarian and technological advancements – with an example of one of the first satellite images of Earth becoming a visual representation of universalist claims and acting as a conceptual frame of the “Family of Man”, of humanity.(V) The way in which humans interact with the other components of the tilt becomes the catalyst for new relationships to emerge, an ever-changing symbiosis between man and nature or man and technology. Relating to Donna Haraway’s theories in A Cyborg Manifesto, the distinction, or better said the lack of distinction, between organism and machine, and with that, the distinction between the natural and the artificial has been made ambiguous by recent technological progress.(VI) Rhomberg refers to this blurring of lines between human and machine and, consequently, the blurring between nature and machine. Her creative process involves multiple stages, moving from analog to digital, from nature to machine, morphing them into each other. She begins with images of analog objects and continues her process through digital sketching, to then return back to the analog process of a paintbrush on canvas. Translated through a visual language assimilating not only physical folds of fabric but also of glitch-art and the digital, Rhomberg brings in the questions of symbiosis or sympoiesis, defined by Haraway as the moment when living things assimilate and interpenetrate one another, work themselves into clusters to which we give names, such as cell, organism or ecological assemblage.(VII)As a quasi-sympoiesis of man, nature, and machine, each component respectively affects the other, and the artist investigates these connections while bringing them back into the analog through the physicality of her process of making.

As the contradictions and connections are presented within the artist’s works, she explores these themes while referencing theories ranging from sixteenth-century art historical discourse to recent technological developments and their impact on socio-ecologic circumstances, such as the aforementioned emergence of satellite imagery contributing to a shift in the conceptual framework of humanity. The past elements relate to drapery and folds in early modern painting, however, they explore materiality through an artificial gaze of abstracted perspectives and a digitally influenced visual language. Rhomberg also explores the aspect of nature, encompassing art history as well as her physical surroundings of today, yet her intense abstraction of the natural elements creates new perspectives, veering away from nineteenth-century landscape painting to which she makes reference. The addition of the symbiosis of human, nature, and machine and their evolving relationships to one another result in a complex visual expression that Rhomberg renders in paint, playing with the boundaries of the analog and the digital. Artificial realities, abstracted nature, analog technology – all of these dichotomic connections are contained within her multi-faceted works which vehemently explore societal and anthropological topics spanning over space and time.

Alexandra Steinacker, London, October 2021

(I) Rose Marie San Juan, ‘Review: Framing the Early Modern Field of Vision‘ in Oxford Art Journal, Vol. 21, No. 2, Oxford University Press (2000), pp. 171-177, p. 173

(II) Ibid. p. 173

(III) Ibid p. 173

(IV) Anselm Franke, The Whole Earth, California and the disappearance of the outside, Berlin: Steinberg Press (2013) [no pagination]

(V) Ana Teixeira Pinto, ‘The Whole Earth: In Conversation with Diedrich Diederichsen and Anselm Franke’ in E-Flux Journal, Issue #45 (May 2013) available online at https://www.e-flux.com/journal/45/60114/the-whole-earth-in-conversation-with-diedrich-diederichsen-and-anselm-franke/

(VI) Donna Haraway, ‘A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century’ in The Cybercultures Reader, ed. David Bell and Barbara M. Kennedy, pp. 291-324, London: Routledge (2000) p. 293 (VII)Devin Proctor, ‘Book Review: Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene By Donna J. Haraway’ in Anthropological Quarterly 90(3) 877-882 (January 2017) p. 879

PERPETUAL »

PERPETUAL »

MIXED FEELINGS »

MIXED FEELINGS »

BEAUTY IN FAILURE »

BEAUTY IN FAILURE »

BREAK »

BREAK »

Kathrin Isabell Rhomberg, Fuzzy Tropical »

Kathrin Isabell Rhomberg, Fuzzy Tropical »

Kathrin Isabell Rhomberg, Tropic II »

Kathrin Isabell Rhomberg, Tropic II »

Kathrin Isabell Rhomberg, Two ridges »

Kathrin Isabell Rhomberg, Two ridges »